Andrew's Brain is about 200 pages. There is one voice - Andrew - talking probably to a mental health professional. The narration is fast flowing , hard to follow and at times it seems pointless. Andrew recounts the death of his first wife, but was that for real?

Once I started mistrusting Andrew's narration, it becomes boring. At least it short! It has some good passages. The master has not lost his touch.

Illustration by Al Murphy for The Wall Street Journal

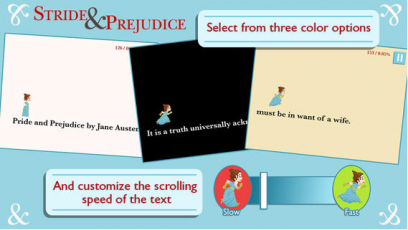

ONE DAY, HUNCHING

in front of a computer screen or squinting at a smartphone to read

anything longer than a tweet will seem barbaric. To engage with text

thoughtfully and comfortably, e-readers and tablets are still the most

evolved gadgets, especially when they're outfitted with the right apps

and Web services.

Implement our simple

system below, and you'll be able to peruse, on your own terms, all of

the long reads that you never quite get around to. Plow through a week's

worth of Web links during a flight. While you're at the salon, sift

through those in-depth stories everyone was talking about on social

media. Help yourself to the tools below, and you won't feel out of the

loop at your next dinner party.

—Erik Sofge

1. Corral Long Web Articles

Illustration by Al Murphy for The Wall Street Journal

What's the best way to beam documents from your computer

to a more reader-friendly device? Erik Sofge joins Lunch Break with a

look at the latest services for e-readers on the go. Photo: Getty

Images.

You can beam them to a tablet or

e-reader and they'll all be waiting for you when you're ready to dive

in. Amazon offers a range of options for sending Web articles to a

Kindle. The easiest to use is the Send to Kindle

plug-in for the Chrome and Firefox browsers, which lets you beam an

entire Web page, stripped of ads, to a Kindle or the Kindle app for

Android and iOS devices.

Another handy solution is the free Web service Pocket ( getpocket.com ).

Like Send to Kindle, you can use Pocket to save articles to a range of

devices. What sets it apart, though, is the ability to send stories by

simply emailing a link to a Web page. (Kindle has a similar feature, but

it requires you to email the article in the body of the message or as

an attachment.) Pocket works with Android tablets and iPads, as well as

standard e-readers from Kobo, including the terrific Aura HD (see

below).

2. Tame Social-Media Mayhem

Illustration by Al Murphy for The Wall Street Journal

If, like many people, you find your

social-media feeds to be impenetrable lists of links that you dread

having to click through, download Flipboard (free, flipboard.com ). This popular tablet app for aggregating Web articles into a magazine-like format is also genius at making a dense

Twitter

feed easier and more enjoyable to scan. Instead of presenting a

list of links, the app elegantly displays previews of each story,

complete with images and snippets of text. Tapping one of the teasers

expands it to a full-screen version of the article in a clean,

three-column layout. Tweets without links appear as a list along the

side of the page.

Flipboard works with

Facebook

feeds, too, pulling together photos, videos and status updates

into a somewhat more organized-looking scrapbook. Best of all, the app

works on just about every major tablet: It's compatible with Android,

BlackBerry, iOS and Windows 8 devices.

3. Wrangle Unwieldy PDFs

Illustration by Al Murphy for The Wall Street Journal

PDFs were designed to be printed on

paper, not viewed on computer screens, but the format is still popular

for sharing documents digitally (especially product manuals, brochures

and anything that was once a booklet). Unfortunately, trying to read a

PDF on a computer, e-reader or tablet can require scrolling to various

sections of the page or zooming in on minuscule text.

Although the Scribd app (free, scribd.com )

is intended for accessing the company's e-book service, it also happens

to be the least frustrating way to read PDFs on an Android tablet or

iPad. Compared with other PDF-compatible apps, Scribd's interface is the

most intuitive: You can swipe across the screen to flip through pages,

and when you hold your tablet in a landscape orientation, the app

displays two facing pages at once, like an open book. As with competing

readers, Scribd lets you search text and zoom out to view all of the

pages as thumbnails. Biggest difference? Scribd does it all more

gracefully.

Which Gadget Is Best for Lots of Text?

From left: Kobo Aura HD, Amazon Kindle Paperwhite and Apple iPad Air

Illustration by Al Murphy for The Wall Street Journal

The Contender: Kobo Aura HD

Text

and images look stellar on the Aura HD's black-and-white, hi-res

screen—better than on any other e-ink reader out there. Plus, the device

has a slightly larger display—6.8 inches diagonal to a typical Kindle's

6 inches—resulting in a "page" that's closer in size to a paperback. $170, kobo.com

Plus: A broad selection of font and formatting options that typography nerds will love.

Minus: A premium price—$31 more than the ad-free Paperwhite.

The Reigning Champ: Amazon Kindle Paperwhite

Compared

to the first Paperwhite, the latest iteration has a crisper display and

a more evenly distributed built-in light. Battery life is impressive:

an estimated 28 hours with the light turned on. Starting at $119, amazon.com

Plus:

The ability to get recommendations from the Goodreads community of

bookworms (who tend to be a lot more knowledgeable than the typical

Amazon reviewer).

Minus: The least-expensive version of the Kindle displays ads when the device is asleep.

The Featherweight: Apple

Although

an e-ink screen is easier on the eyes than a tablet's backlit display,

the iPad Air is by far the slickest way to access dedicated reading

apps, like those for newspapers and magazines. Starting at $499, apple.com

Plus: Weighing only 1 pound, this is the first full-size tablet that can be comfortably held in one hand for long stretches.

Minus:

The iPad Air's battery life (rated at 10 hours) is impressive for a

tablet but trails e-ink readers like the Aura HD and Paperwhite.

Buffets for E-Bookworms: All-You-Can-Read Subscriptions

Think of the latest crop of e-book subscription services as

Netflix

for bibliophiles. For a low monthly fee—usually less than the

cost of a single e-book—you can read as many titles as you like.

Oyster ($10 per month, oysterbooks.com )

offers a solid selection and pleasing interface. Although many of its

100,000-plus e-books are obscure, you'll find over 1,000

New York Times

best-sellers in the mix, according to the company. The Oyster app

is currently only compatible with iPad (and iPhone), but an Android

version is in the works for release next year.

Scribd ($9 a month, scribd.com )

is similar to Oyster in price and selection, but its app isn't quite as

polished. Still, if you own an Android tablet, this is your best

option.

Finally, there's the Kindle Owners' Lending Library, which is included in an Amazon Prime membership ($79 per year, amazon.com ).

The fee includes access to one book per month from a list of some

400,000 titles. The collection is large but includes only about 100 New

York Times best-sellers, according to Amazon. Access to this feature

requires a Kindle device (the apps for Android and iOS are not

compatible). At $6.58 per month, it's not worth signing up for Amazon

Prime just for the books alone, but if you're already a member for the

unlimited video and free shipping that are included with the

subscription, the lending library is a modest perk.